The story of the Königsberg is a fascinating

one, and that of her main armament even more so. Not only did these guns serve

on the ship in the warm waters of the Indian Ocean, but also on the dusty plains

and the rain forests of East Africa. Today one of these remarkable guns rests at

the western approach of the Union Buildings in Pretoria.

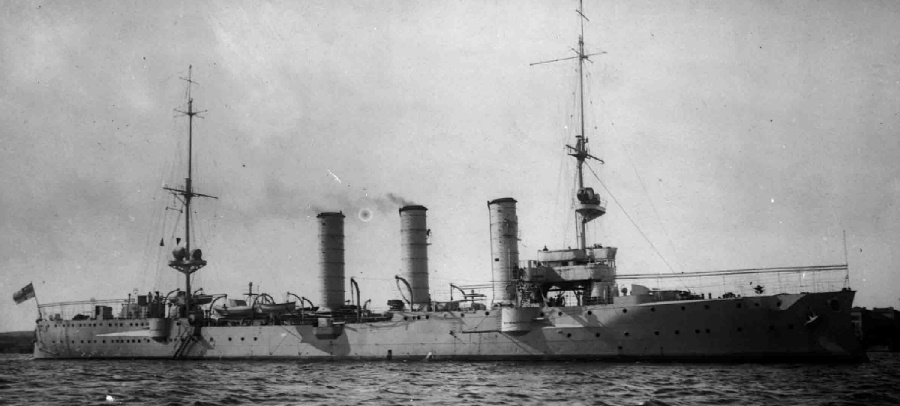

SMS Königsberg was the first of a new class

of fast well armed Town Class Cruisers (Kleiner Kreuzen) displacing 3,500 tons,

built for the German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) at the turn of the 20th century.

Launched in 1905 she was a sleek, three funnelled predator, carrying a main

armament of ten 10,5 cm quick firing guns (German: 10,5 cm Seekanone or 10,5 cm

SK). She initially served with the Baltic Fleet where she also acted as escort

to the German Kaiser’s Royal Yacht Hohenzollern before being laid up at Kiel in

1912. In late 1913 the German East Africa government requested a suitable

replacement for their elderly sail and steam corvette, S.M.S. Geier then on

station. Four months later on 25 April 1914 a re-commissioned Königsberg

commanded by Fregatten Kapitan Max Looff left the Kiel naval base for East

Africa to reaffirm German naval power in the Indian Ocean. After arriving at Dar

es Salaam on 6 June, Königsberg, played host to innumerable German and African

visitors in ports along the colony’s coastline. Little did her crew realise that

East Africa was to be, for most of them, home and headquarters for what remained

of their short lives.

On 28 June 1914, the Archduke of Austria was

assassinated in Sarajevo, and as the political situation in Europe slid towards

open war, the Germans in East Africa began to weigh their options. Looff's

immediate goal was to ensure his ship was at sea if war came. The British were

aware of the new threat on the coast, and in case of war would blockade Dar es

Salaam. As the latter part of July passed, Königsberg completed a series of

gunnery training exercises and steamed back into harbour for an overhaul to

wartime readiness. All wood furnishings were removed, lacquered panelling

stripped away and coal and supplies poured into every empty space. By July 30,

all was nearly ready and Looff spent time ashore coordinating his plans with the

Colonial Army, commanded by the famous General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. German

freighters in the area had been ordered to bring in their spare coal, and two

were in harbour at that stage. One of these, the 2,500 ton Somali, was pressed

into service as Königsberg's seagoing supply depot. On July 31, the steamer

Tabora arrived with news that the British Cape Squadron, based at Simonstown,

South Africa, with their three cruisers under Vice Admiral King-Hall was due at

Zanzibar the next day. There was now no more time for planning if Königsberg was

to avoid being trapped in the harbour. By 4:30 that afternoon she cast off and

made her way out into the Indian Ocean.

The Königsberg was ten miles out to sea and

evening was falling when the officer in the foremast called down - three ships

approaching! The Cape Squadron had arrived, only to see their objective steaming

out to sea. All three British cruisers; H.M.S. Hyacinth, Pegasus and Astraea

converged on the Königsberg and took up station around her - Astraea to port,

Hyacinth astern and Pegasus ahead. If word of war came then Königsberg could

hardly have been in a worse situation. Looff considered his options and while

the gunners would have been at the ready, he ordered his chief engineer to fire

up all the boilers without making extra smoke. After 45 minutes the Königsberg

had steam for her full speed of 24 knots and now only had to wait for whatever

chance might come to use it to escape. Until such opportunity arrived, she

cruised along at 10 knots, giving no sign of other plans. Not long after, a

squall suddenly blew in from the southwest, and without warning Königsberg was

blanketed by driving warm rain, all her "escorts" disappearing from view.

Instantly orders went out and the cruiser made a 180 degree turn, churning a

great knuckle of water behind her as she sped back on a reciprocal course. As

she cleared the squall, Königsberg passed the Hyacinth, already making heavy

smoke as she vainly tried to bring up steam for full speed. Looff turned south

for an hour and then headed out to sea at full speed for the rest of the night,

consuming a large quantity of valuable coal in the process. King-Hall was left

to his own fury at letting the German cruiser escape from under his nose, while

Looff was left to wait for war, in a cruiser already looking for coal to top up

her bunkers.

Four days later, on August 4, the Königsberg

was making her way through heavy seas off Cape Guardafui when she received a

wireless code message declaring that Germany was now at war with England, France

and Russia. This meant that in the vast open space of the Indian Ocean, she was

now alone and hunted by a numerically superior foe. But she herself was designed

to hunt, and Looff was out for prey. After contacting as many German merchant

ships as possible, to both notify them of war and ask for coal, Königsberg

headed for the main shipping channel from the Red Sea to India which ran just

north of the Horn of Africa. Within several hours of daylight she encountered

three German steamers, the last of whom tried to evade the cruiser thinking her

to be British. This short pursuit wasted more coal, and none of the steamers had

any to spare. Finally, after passing a Japanese freighter, Königsberg drew her

first blood when she came upon the British steamer City of Winchester. The

steamer rang up all stop and prepared a welcoming party for the British cruiser

she thought Königsberg to be. Only when the German officer arrived on deck did

the Winchester's crew realize their dreadful mistake. This, the first British

merchant ship to be taken by a German man-of-war, was also carrying most of the

1914 Ceylon tea crop, making it a double blow for the British.

After scuttling the City of Winchester at

Hallaniya Island off the Oman coast, Königsberg's coal situation was even more

of a concern and she turned back to the main shipping lane but found nothing.

The British had reacted swiftly to the disappearance of the City of Winchester

and diverted all ships away from the area. Also, the Japanese freighter had

recognized the Königsberg for what she was and radioed British authorities.

While the upheaval caused by his cruiser might have given Looff some comfort,

his concerns were increasingly focused on finding more coal and fresh water.

Fortunately for him, the second rendezvous with the Somali at Ras Hafun on the

Somaliland coast went mostly as planned, and by August 24 the Königsberg was

underway again with full bunkers.

Cut off from radio contact with Dar-es-Salaam

(the radio station at the capital being destroyed during a British naval

shelling of the city), Looff headed for Madagascar where he hoped to intercept

French shipping. Early on the morning of August 29 the German cruiser steamed

into the bay at Majunga, only to find a Red Cross station and no ships. The

entire area had been evacuated. Again, the locals believed the Königsberg to be

British, and only when she was steaming back out of the bay without anchoring

did the local radio send out alerts that the Germans were in their harbour.

By now Königsberg's coal supply was down to

250 tons and again she met the Somali, this time at Aldabra Island, but the

coaling effort was called off due to rough seas. Coal was not Looff’s only worry

as the ship also required some work on her engines. With the situation becoming

critical, it was decided that both ships would head for the Rufiji River Delta.

The delta had recently been charted by the crew of the survey ship Möwe who

discovered the river, formerly considered unnavigable, actually had several deep

channels. On the morning of 3 September Königsberg passed the bar at the mouth

of the Rufiji River and steamed quietly up the Simba-Uranga channel to Salale.

Once the German authorities at the nearby

customs station recovered from their shock at the cruiser’s unexpected arrival

they quickly advised Dar es Salaam of the cruisers whereabouts and that she

required coal and supplies. Looff was also able to gather the latest news on

world and local events, the most important of which came on September 19. A

coast watcher reported he had seen a British cruiser steam into Zanzibar

Harbour. The news was relayed to Looff who having replenished his bunkers

decided to head to Zanzibar, and destroy the lone British cruiser. Judging by

the watcher's description of the British ship, it must be the Pegasus or the

Astraea. In reality, it was Pegasus which had returned to Zanzibar for

maintenance.

A Third Class cruiser of the Pelorus class,

Pegasus had been launched in 1897 and displaced 2,135 tons, while her 4 inch

guns were no match for the Krupp 4 inch guns on Königsberg. Because of a

combination of boiler troubles common to the class, and the fact that she had

been burning sulphurous Natal coal, she to put in at Zanzibar for desperately

needed repairs. It was considered a safe move by British authorities, convinced

that Königsberg was no longer in East African waters. They were wrong.

Königsberg sailed that afternoon and by late

evening, was steaming for Zanzibar at her economical speed of 10 knots. Higher

speeds caused sparks to shoot from her funnels, something they wished to avoid

that night. By four o'clock in the morning, they were off the southern tip of

Zanzibar and passing between the reefs. The tug Helmuth on guard duty was

disabled by a shell. As they approached the village of Mbweni they could see

Pegasus at anchor off the Eastern Telegraph Company offices at Shangani Point..

At a range of five miles, Königsberg ran up her battle flags and opened fire

with her five port guns. Within eight minutes Pegasus was out gunned and on fire

with heavy casualties. Her captain, Commander John Ingles struck the colours and

surrendered. The white flag was seen by Looff who ordered a cease fire and

departed. The Pegasus had been hit numerous times and the ship was slowly

sinking. Despite efforts to beach the ship, Pegasus sank at two thirty that

afternoon with a loss of 38 killed and 55 wounded. .

Leaving Zanzibar, Königsberg suffered a

broken cross head on one engine and together with steam leaks caused by the

bombardment, Looff had little alternative but to postpone his plan for a return

trip round the Cape to Germany, while he effected repairs in the Rufiji. Only

the railway machine shops at Dar es Salaam would be able to machine the parts

needed and so, twenty-four hours after her departure, Königsberg was back in the

delta, the only safe place on the coast for her to lay up. The delta was

bisected by numerous channels, and the Germans were the only ones who knew that

several of them were navigable. In case of emergencies, Königsberg would have an

escape route. In the meantime, the engine parts were sent overland to

Dar-es-Salaam by ox cart. To complete her disappearance Looff had the top masts

dropped and camouflaged the remainder as trees, while some of the ship’s light

weapons were moved ashore to keep possible British landing parties at bay. Later

they were joined by forces from the land army who garrisoned the local islands,

creating a safe zone around the raider. For now, she would be safe.

Looff was unaware of several events

developing elsewhere. Two days after his attack at Zanzibar, the German cruiser

Emden shelled the port of Madras in India, causing huge panic and setting some

fuel tanks ablaze. This double blow to British pride was not to be stood for,

not to mention the strangling effect these German actions had on shipping. The

six inch gun cruiser H.M.S. Chatham was ordered to East Africa from the Red Sea

to seek and destroy Königsberg. The first break for the British occurred when

Chatham searched the German liner Präsident and discovered an order for

shipments of coal to be delivered to the Rufiji Delta and the cruiser H.M.S.

Weymouth intercepted the German tug Adjutant with a chart showing Salale. Soon,

reports began trickling from locals in the Rufiji area of a German ship moored

there and on the afternoon of October 20, Chatham anchored near the Kiomboni

branch of the delta to send a landing party ashore. Fortunately for them, it was

at a place where there were as yet no German fortifications. Chatham closed the

delta mouth and spotted the Somali masts rising above the green canopy of the

river delta's forests, her cover was blown.

On the morning of November 30, Chatham zeroed

in on what they now knew to be the Somali’s masts and fired. Somali was hit

several times and soon began to burn and Looff moved Königsberg further up the

delta, out of range having suffered no damage during the day. Although the

mechanical problems had been repaired, the situation was now grim, Königsberg's

hiding place was blocked by three large, fast modern cruisers, and she lacked

coal for a high speed run. Captain Drury-Lowe on board the Chatham had been

given explicit orders to destroy the Königsberg at all costs. This was to be the

start of an eight month long impasse, during which Königsberg was unable to

escape from the delta, while the British were unable to get close enough to

bombard her. More entrenchments were dug throughout the delta, creating a

fortified zone which no British land force could hope to secure. On the British

side, there were several attempts to bring aircraft in for reconnaissance and

bombardment. The former worked occasionally, sometimes causing alarm when they

reported Königsberg with steam up and ready to run for the open ocean. The

latter never had a chance, as the aircraft were so unreliable that their main

goal was to stay in the air, not dropping bombs! After a few encounters with

these snooping aircraft, Looff arrayed a series of light cannon and machine gun

positions as an anti-aircraft defence. These proved effective and brought down

at least one of the British planes.

On New Years Day a message was sent to Looff

from H.M.S. Fox, "We wish you a Happy New Year and hope to see you soon."

Looff replied, "Thanks, same to you, if you wish to

see me, I am always at home."

In April 1915, the Kronborg, a "Hilfschiff"

(or blockade runner) bearing supplies for Königsberg and the land army, arrived

in the Indian Ocean after a long voyage from Germany. Disguised as a Danish

freighter, she was carrying 1,600 tons of high grade Ruhr coal for the cruiser,

as well as hundreds of rounds of ammunition for the 10.5 cm guns, machine tools,

cutting torches, clothing, fresh and canned provisions and a variety of other

supplies. She also carried over a million rounds of small arms ammunition,

rifles and machine guns for the land army. The British however, knew of her

arrival, and thanks to diligent eavesdropping on German radio transmissions,

they had discovered her purpose. The ship reached Manza Bay near Tanga, when the

British cruiser Hyacinth appeared from the south. The captain of the Kronborg

brought his ship into the bay at full speed, and ran it aground before setting

fire to the deck cargo. The Hyacinth attempted to put the fire out but retreated

and shelled the ship. The Germans promptly sent messages in the clear announcing

the destruction of the ship, and that they had mined the bay. This last bit of

news had the effect of keeping the British away long enough to allow the salvage

of the cargo in her submerged holds. By the time the British returned a few

weeks later, they discovered to their dismay the Germans had salvaged everything

except the coal. The logistics of moving the coal to the Rufiji would have been

impossible with the facilities available.

The loss of the coal meant that Looff and the

Königsberg would be confined to the delta. By this time the ship was now burning

mangrove wood cut from the surrounding swamp by local labour to maintain power.

Their fear was that a second Hilfschiff would get to the Königsberg, allowing

her to head back into the Indian Ocean, but the second ship Marie did not arrive

until the following year. What he did not know, was that the British had begun

systematically charting the delta and the complex web of defences with the help

of a South African hunter, Peter Pretorious. The British Admiralty also

dispatched two ex Brazilian Navy monitors, the Mersey and Severn, to East Africa

where they arrived in June 1915 after a long and difficult tow from the

Mediterranean. By this time the crew of the Königsberg had been reduced by a

third in order to supplement the land army after convincing the navy that the

crew were more valuable fighting on land, instead of resting idly in the delta.

The British were unaware of these developments, but they knew Königsberg was

awaiting a second Hilfschiff.

On July 6, 1915 the two monitors finally

executed the operation carefully planned and rehearsed over several weeks.

Severn and Mersey, supported by warships at the delta mouth, headed up the

Kikunja branch of the delta. Looff was soon aware of their arrival through his

network of lookouts. At 06:23 the monitors opened fire using a spotter plane to

locate the fall of shell. Königsberg's return fire was accurate, due to the

network of lookouts linked by telephone who passed the monitors position to the

cruiser. The British fire was inaccurate due in part to the signalling system

used between the planes and monitors. At 07:40, a shell from Königsberg hit the

Mersey's forward six inch gun, knocking it out and almost blowing up the ship.

She was saved only by the heroic action of crewmen who threw a burning shell

into the river. Near misses continued to shower the monitors with shrapnel, and

after scoring only four hits on the Königsberg, the monitors retired on the

falling tide. Immediately after Severn moved off, five shells from the cruiser’s

guns landed right where she had been moored. Had they hit her, this perfect

group of shells would have wrecked or sunk the small monitor. The British

counted their luck, they had fired 635 six inch shells and scored four

inconclusive hits on the Königsberg. The Mersey had lost one of her two main

guns and Severn missed being blown out of the water by what her captain called

blind luck.

For four days all was quiet, but early on

Sunday, July 11, the aircraft began circling Königsberg, announcing the renewal

of a second attack. By 10:40 the monitors were in the entrance to the river and

by 11:30 the Königsberg had begun firing, hitting the Mersey with two shells,

putting the rear main gun out of action. With the Mersey now completely

incapable of returning fire, the Königsberg switched attention to Severn, who

held her fire under the rain of shells until the second spotter plane arrived at

12:30. The carefully rehearsed signal system between ship and plane worked

perfectly the second time and Königsberg was severely damaged with a number of

casualties and damaged guns. The loss of the telegraph line to the ship from the

lookout posts meant she was firing blind and unable to keep up the same rate of

fire. Within a short time, a hit from Severn ignited ammunition in the

Königsberg's after magazine, causing an explosion and a fire. Other hits killed

a number of the crew and damaged the bridge, injuring Looff and all but one man

present. Finally, one of the two remaining guns fired its last round of shrapnel

ammunition at the spotter plane, bringing it down in the river. As shells

continued to rain down, First Officer Koch rigged a torpedo head as a scuttling

charge and at two o'clock that afternoon Königsberg heaved slightly as the

torpedo detonated. The blast tore open the cruiser's hull and she heeled to

port, sinking into the mud with her upper works just above the waterline. She

had occupied the Royal Navy for nearly a year tying up twenty ships and ten

aircraft and consuming nearly forty thousand tons of coal. Looff signalled

Berlin: “Königsberg is destroyed but not conquered.”

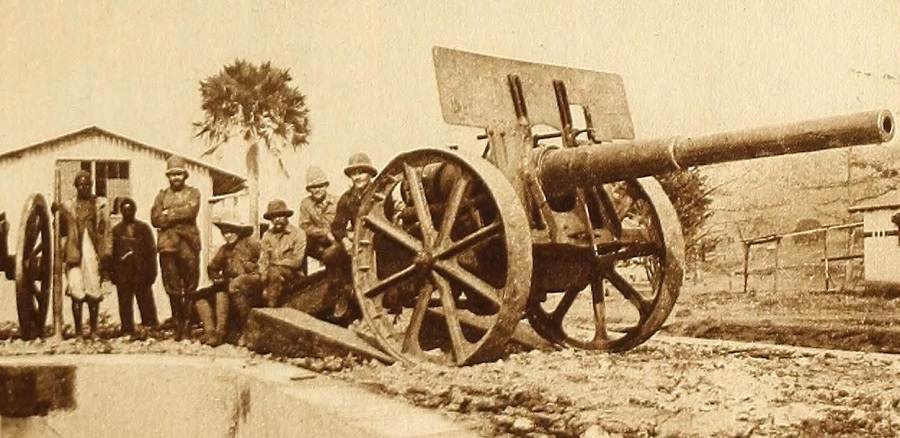

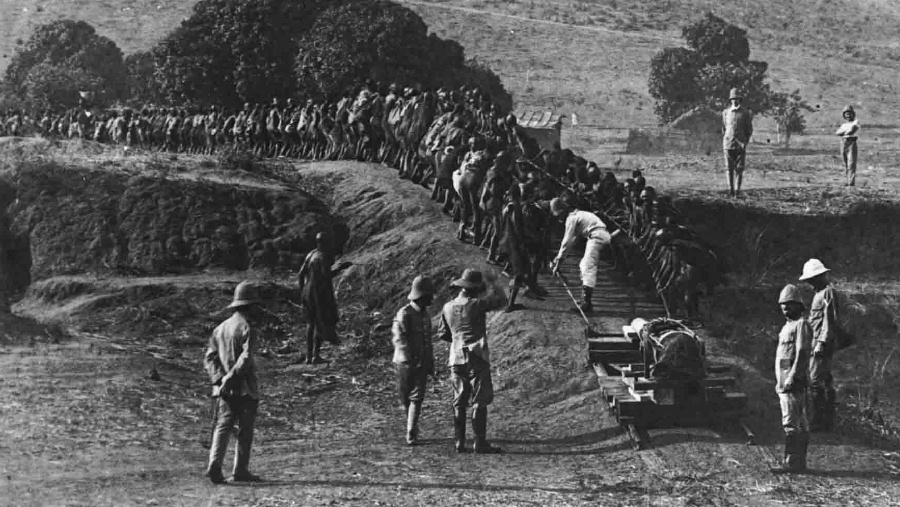

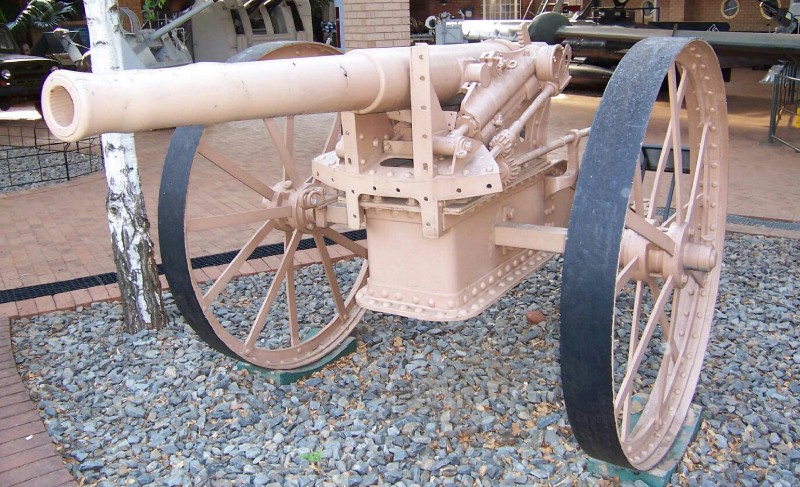

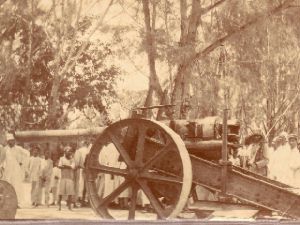

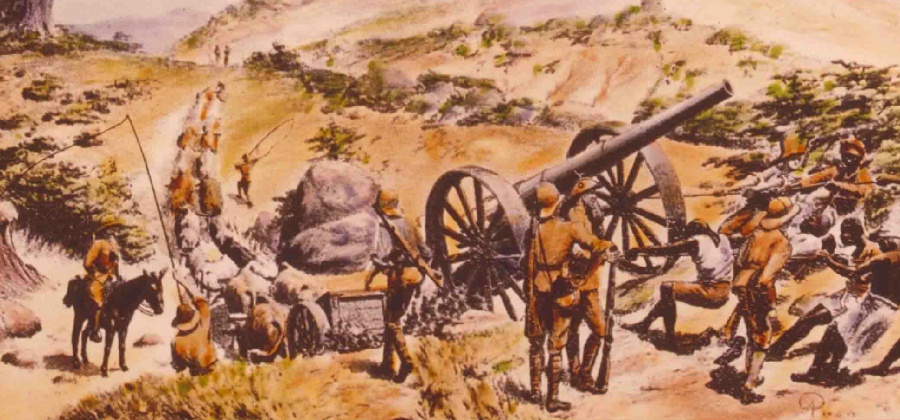

These were prophetic words as the Königsberg,

although doomed as a fighting ship, still had plenty of fight left in her. From

Dar-es-Salaam the order went out to salvage everything of use from the ship.

Especially her main guns which were used by the German land forces to supplement

their field artillery. The heavy guns were recovered and dragged on carts

through the bush to the capital. There they were cleaned and carriages

constructed from boiler plate at the railway workshops. Some guns were intended

for fixed defences and received no carriages. Around 1,500 shells were salvaged

from the Königsberg and the Kronberg and shared out between the ten guns.

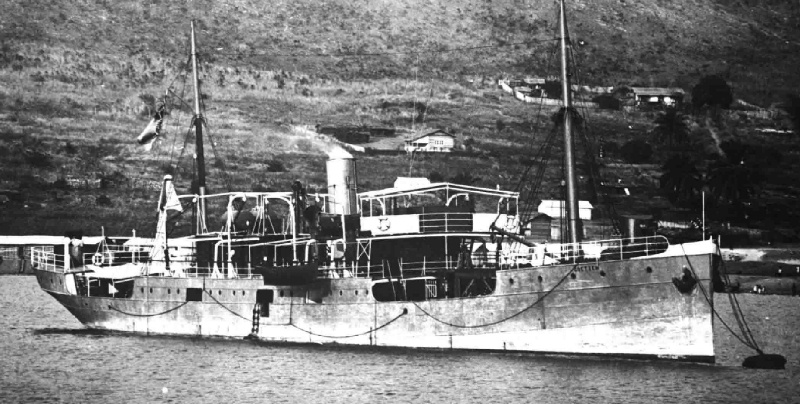

From Dar-es-Salaam, the guns were despatched

to various corners of the colony where they began their second career. They were

skilfully operated by sailors from the Königsberg, now facing the African

jungles instead of the open seas. One was mounted on the Goetzen, the largest

steamer on Lake Tanganyika but later removed for use on land. The refurbished

guns gave good service to the German ground forces, being much valued for heavy

artillery support. Their shortcomings were that they were heavy and not very

mobile, while their armour piercing shells were not intended for land use, and

often buried themselves deep in the ground before exploding. South African

troops fighting at Kondoa Irangi in July 1916, noted their satisfaction with

this state of affairs. There was however some casualties to these guns and their

persistent shelling were trying to the nerves.

As the war rolled on over East Africa, the

Germans were forced to abandon or destroy these heavy guns. Their intrinsic lack

of mobility became a liability as the Schutztruppen and their African Askari

troops moved into a war of movement in the vast regions of Southern Tanzania.

The Königsberg guns were abandoned or captured as follows :

1 at Kahe, March 1916

1 at Mwanza, July 1916

1 at Kigoma, July 1916

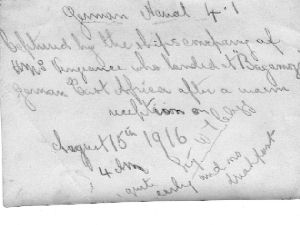

1 at Bagamoyo, August 1916

1 at Kondoa Irangi, August 1916

1 at Tabora, September 1916

1 at Kahima, September 1916

1 at Mahiwa, Octobery 1917

1 at Massasi, October 1917.

1 at Kibata, October 1917

Most of the guns were abandoned or destroyed

after they ran out of ammunition by their crews to prevent them from falling

into enemy hands. After the end of hostilities the captured Königsberg guns were

distributed as trophies and the following locations are known :

1 to Pretoria, South Africa

1 to Mombasa, Kenya

1 to Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania

1 to Kampala, Uganda

1 to Leopoldville in the then Belgian Congo

1 to Stanleyville in the then Belgian Congo

Of the Königsberg's original crew of 350 men,

only 15, including Captain Looff, survived the war to return to Germany.

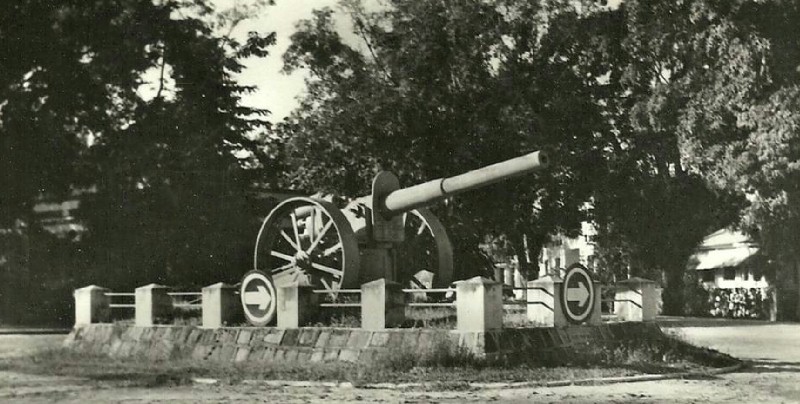

Today only the two guns in Pretoria and Mombasa are known to exist, both are

mounted on similar heavy wheeled field mountings, possibly being those captured

in a better condition (*since this article was written a third gun has been

rediscovered, seen above in Jinja, Uganda). Other items including parts of a gun

and a sighting mechanism are preserved at the South African National Museum of

Military History in Saxonwold, Johannesburg. In the Imperial War Museum, London

is the ships steam whistle and the Inclinometer is displayed at the Fleet Air

Arm Museum at Yeovilton. A few shell cases are also exist in many parts of the

world.

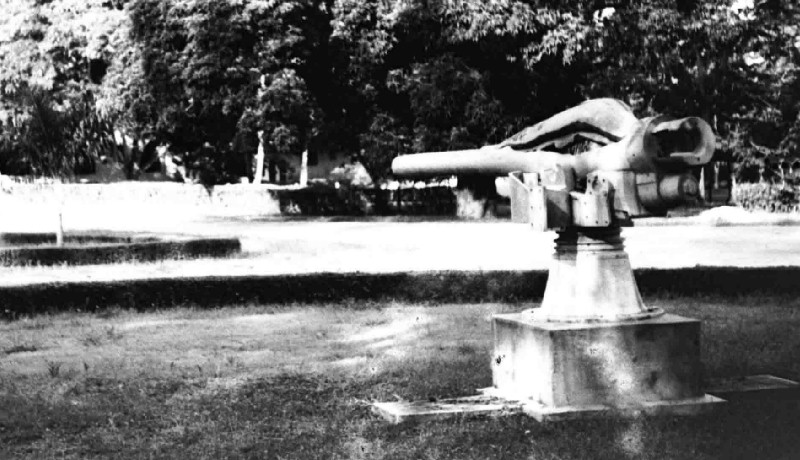

Inspection of the gun located in the grounds

of the Union Buildings in Pretoria, revealed that it is inscribed with the

serial number 369 as well as “FRIED KRUPP, ESSEN”, identifying it as a gun made

by this famous German firm. A bronze plaque attached to the carriage states that

it is the gun captured at Kahe, but this can not be as the Kahe gun was fitted

on a wooden mounting, not a wheeled carriage and was found blown up by the

Germans before they abandoned it. The gun’s naval origins are easily

discernable. The long barrel and heavy cradle type recoil system were designed

for shipboard use. The gun is missing its breech block pointing to the

conclusion that it was abandoned by the Germans once it had used all the

ammunition available. A strong sheet metal carriage supports the gun, but a

closer look reveals the carriage to be very utilitarian in nature. When mounted

on a cruiser the gun had a range of 12,000 metres. The shell weighed 17.4 kg and

the gun muzzle velocity was 600 - 650 m/s. On land the gun would have weighed

around 4,000 kg. At one time the gun was painted a dark green colour but has

been since repainted in maroon. The original colour scheme would probably have

been the same as on the cruiser, i.e. a light sea grey, but it is possible that

it was re-painted to camouflage it during its service on land. Clearly this was

a powerful and unique gun, and one which ought to be preserved not only as a

reminder of the Königsberg’s adventures, but also of South Africa's contribution

to the First World War.

Two sidelights on this story should also be

mentioned. Firstly the Königsberg also carried two smaller 8,8 cm guns (German:

8,8 cm Seekanone L/30) in her hold, probably to equip and transform a merchant

vessel into an armed merchant cruiser. These guns were also used on land and

one, captured in September 1916, is currently on display at the South African

National Museum of Military History.

Secondly, if we cast our minds back to the

Königsberg's most famous victim, the British cruiser H.M.S. Pegasus, then there

is another twist in the tale. Six of the eight guns on Pegasus were also

salvaged by the British and mounted on land carriages. The two opponents thus

met again, this time on land. Today one of the "Peggy Guns" stands next to the

Königsberg gun (the "Bagamoyo" gun) at Fort Jesus in Mombasa, Kenya - two once

wartime foes now rest peacefully together.

Sources:

Brown J. A. They Fought for King and Kaiser - South Africans in German East

Africa 1916, Ashanti Publishers, Pretoria, 1991

Hall D. D.

German Guns of World War I in South Africa, S A Military History

Journal, Vol. 3 No. 2, December 1974

Hoyt E. P. The Germans who never lost - the most amazing story to emerge from

World War I, Leslie Frewin, London, 1969

Keble-Chatterton The Konigsberg Adventure. Hurst & Blackett. 1930

Miller C. Battle for the Bundu. MacDonald, 1974

Patience K. Zanzibar and the loss of H.M.S. Pegasus. Published by the Author.

1995

Patience K. Königsberg. A German East Africa Raider. Published by the Author.

2001

Patience K. Shipwrecks and Salvage on the East African Coast. Published by the

Author. 2006

German Eyewitness Sources

"Kumbuke, Kriegserlebnisse eines Arztes"

by August Hauer, Deutsch-Literarisches Institut J Schneider, Berlin-Tempelhof

1935

"Mit Lettow-Vorbeck durch Afrika" by Dr. Ludwig Deppe, August Scherl Verlag, Berlin 1919

"Meine Erinnerungen aus Ostafrika" by Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, KF Koehler Verlag, Leipzig 1920

"Erlebnisse eines Matrosen auf dem Kreuzer Königsberg sowie im Feldzug 1914-18 in DOA" by Rudolf Viehweg self published with Buchhandel Krüger & Co,

Leipzig 1933

"Kriegserinnerungen aus DOA 1914-1917" by

Hermann J Müller, Privately Published

"Geraubtes Land" by

Werner Schönfeld,

Alster-Verlag, Hamburg 1927

"Lebensbericht 5. Die Schiffsgeschütze

als Artillerie der Kaiserlichen Schutztruppe" by Hans Apel, unpublished

personal memoirs

"Erlebnisse eines Matrosen auf dem Kreuzer Königsberg sowie im

Feldzug 1914-18 in DOA" by Rudolf Viehweg, Buchhandel Krüger

& Co, Leipzig 1933

"Vierzig Jahre Afrika 1900-40" by Carl Jungblut,

Spiegel Verlag Paul Lippa, Berlin-Friedennau

1941

"In Monsun und Pori

Safari" by Richard Wening, Verlag, Berlin 1922

"Kriegssafari , Erlebnisse und Eindrücke auf den Zügen Lettow-Vorbecks

durch das östliche Afrika" by Richard Wenig,

Verlag Scherl, Berlin 1929

Other German Sources

"Die Operationen in

Ostafrika im Weltkrieg 1914-1918" by Ludwig Boell,

Verlag Walter Dachert, Hamburg 1951

"Kampf im Rufiji-Delta, Das Ende des Kleinen

Kreuzers Königsberg" by RK Lochner, Wilhelm Heine Verlag, München 1987

Links to Forums

There are two forums where these guns have been discussed extensively with many

photographs-

Axis History Forum Discussion on the SMS Königsberg Guns

Panzer Archiv Forum Discussion on the SMS Königsberg

Guns in German

One of the Königsberg Guns being moved across East Africa